Changing Main Street Requires Change in Thinking

I once heard someone say that in order to understand what the driving force behind a place is, look to the skyline. The tallest and most prominent buildings signify two things: what’s important and who’s in power.

In rural places, main streets dominate the skyline. Buildings there tell a visual tale of commerce and entrepreneurship, with towering parapet walls, decorative cornices, and large storefront windows. Main streets were the economic spaces and opportunities to stock up on needed tools, equipment, textiles. They were locations to meet and negotiate with other businessmen. Whether services or products, a town’s main street was the historical location of commerce.

Early photo of Main Street, Lyons, NE. Photo/Bill Hedges archive.

These were also places of social interaction, where farm families might see each other once a month during a weekend square dance, or come in each Saturday evening for egg and daughter night. Main Streets were the central hub of activity, a place to bond with neighbors and engage in cultural activities.

Today’s main street skyline tells a different story from the turn of the century. Imagery of boarded up buildings, brick and mortar shops now used for storage, or atrophied infrastructure are now a common characterization of rural America.

I’ll spare you the sadistic indulgence of ruin porn.

The material physicality of these buildings outlived their original purposes. Prominent brick and mortar, don’t-make-em-like-they-used-to infrastructure still stands tall on main streets. Some have been repurposed many times over as new uses came about. Yet many are unoccupied, and some of them are atrophying. If walls could talk. Those long-standing mom and pop buildings have weathered the decades, through a post-Fordist economy to the age of internet and a vertically integrated agricultural sector. The landscape of main streets across the US has long since changed just as all of these factors have changed the social, economic, and political order of rural communities.

This presents some unique contemporary problems. When those spaces that once hosted the heart of social connectivity and commerce now sit unoccupied, there is an aesthetic disconnect. What do these buildings now say about what’s important, or who’s in power?

A main street serves as the visual pulse of a local community. If a quick drive down main street shows signs of neglect, it’s easy to attribute pejoratives to rural places. Unoccupied buildings give the sense that the place is undesired, abandoned, or that there is a lack of pride in the community.

I think the main street critique strikes a vein that runs much deeper than an annoyance of property owners neglecting to maintain what is theirs. When the very heart of a community has been designed around main street, and that public center is dotted with spaces that sit empty or are decayed, there is a great disjuncture between the historic aesthetic and the contemporary use of the space. How can a main street both represent social connectivity and vitality yet be riddled with signs of atrophy?

Main streets are inextricably linked to town identity and the imperishable State and serve as a symbol of American roots or the utopian community. Symbols are created with the intent of everlasting endurance, a constant to be believed in. Any breakdown of this representation poses a threat to the fantasy of immortality. This is why main street atrophy is more than annoyance or sadness. It arouses deep primal fears and grief with the fall of each building. The death of rural main streets thus provokes in individuals an existential crisis. A main street in atrophy is sacrilege, akin to burning the American flag.

A shift in thinking and action is needed in order to overcome the weight of despair in such a crisis. Rather than giving up hope on a troubled main street, rural communities can and should embrace alternative methods to tackle the issues head-on. This starts at an individual level, with each community member having the capacity to be an agent of change. Philosopher Peter Wessel Zapffe wrote in his 1933 essay The Last Messiah that there are four common tactics humans put to use, which he defined as isolation, anchoring, distraction, and sublimation. If we take a look at each of these in the rural context, there is one method particularly helpful for altering the state of main streets for the better, and three that don’t do much good to resolve any contemporary issues of the changing rural landscape.

The first of them, isolation, is a dismissal of negative thoughts and feelings, an ignorance-is-bliss code of living. This, however, does nothing to address the underlying issues of small town main streets or work to create positivity where there is negativity; it neglects to recognize any aesthetic dissonance. Anchoring fixates around points of assurance, of things that are thought to remain constants in life. Because anchoring falsely clings to what seems constant in an ephemeral world, this is particularly problematic if a tenant of one’s life is a belief in an everlasting State or the unchanging main street. Distraction is a conscious attempt to escape from the thoughts and feelings causing internal strife. It’s a look-the-other-way kind of practice that Zapffe said can lead individuals back to despair. When Main Street is your town’s central corridor to human activity, it’s hard to ignore that space and it’s use.

The rarest of these protective forms is sublimation, which transforms negative situations into a valued experience through use of aesthetics. Instead of denial and repression of the short-lived nature of all things, sublimation can embrace ephemerality for use in creating new forms of being on our main streets. This could be an author writing a tragedy, or an artist creating a pop-up intervention. Ultimately it’s important to note that the artist – the cultural producer and aesthetic expert – has a valuable role to fill here. Artists have the ability to shift the current forms of our main street spaces into connective places full of vitality.

While rejuvenating downtown buildings may restore new anchoring points for people to latch onto — a revival of the symbolic everlasting Main Street, of sorts — that is not necessarily the point. Artists can both create new beacons of hope while also embracing change and mortality. While the very act of creating is a triumph over atrophy and death, I think the most remarkable aspect of the work of an artist is in changing the forms of living that happen on our main streets.

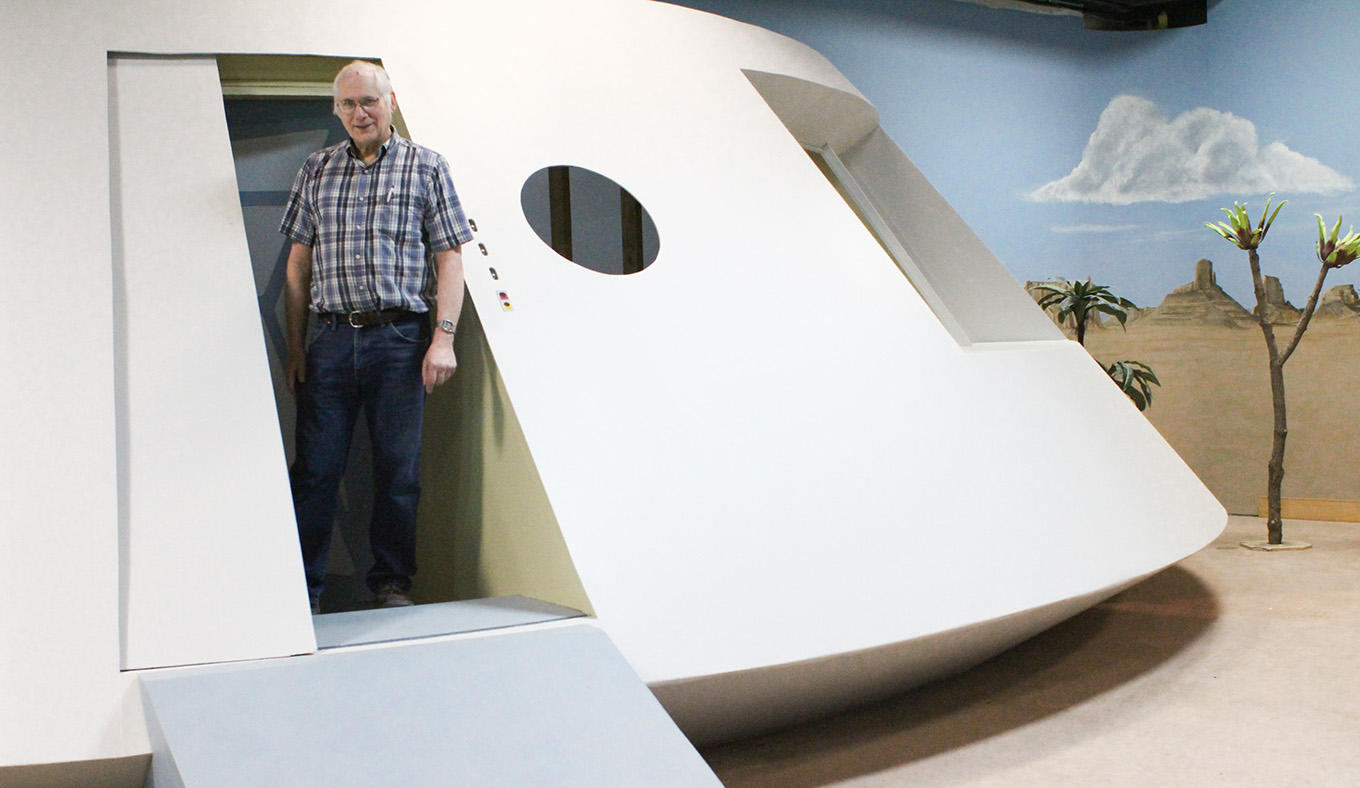

Storefront Theater, Lyons, Nebraska. Photo/Jamie Horter.

The spaces we enter inform our actions and interactions with others. Historically, Main Streets have served both as commerce centers and as the public commons. Empty, unused spaces provide prime opportunities for artists to transform culture through the transformation of space. The careful, astute design of a space can create natural points of connectivity among citizens and potentially move citizens into new roles within their communities. Additionally, public spaces can stir within us an awakening out of our distractions and into just being. They have the ability to improve our quality of life through cultural enrichment and meaningful connection to community.

As proponents of main streets work to bring business back to empty buildings, our rural towns could benefit from more than economic development alone. Having a healthy mix of local businesses is important to small town life, but the quest to revitalize economically should not marginalize the need for spaces that enhance culture. Places of public interaction do not need to be conducted under the umbrella of a monetary transaction; instead, main streets can provide spaces where the very acts of community dialogue and interaction are the sole priority. Why not create a different kind of main street, one that prizes community connection? Such cultural spaces are distinctly different from corridors based on shopping or tourism, as the creation of a space or interactions in a space are based upon social engagement, not economic order. Public participation is key to completing the space, which brings locals back to main street and creates experiences individual to each town. Thus, the ways in which artists create culture on main streets is part of what makes that town unique.

Cosmic Films Studio, Lyons, Nebraska. Photo/Jamie Horter

Spaces define our forms of living: how we go about our lives, the connections we have with others, who is able to participate in society. Rural communities can utilize their empty main street spaces to create new forms of living in rural places that are fitting for contemporary times. Main street spaces can be restored as sites of social connectivity, dialogue, community action, and transformation. The bottleneck to downtown revitalization is not empty main street infrastructure; that is an opportunity. The issue lies in the current vision for how to revitalize main streets and having mechanisms in place to allow transformation to happen. I’ll tackle that issue in another post.

Imagine a rural town where the main street skyline speaks of cultural revolution. Unused buildings become transformed into vital points of interaction and cultural production from within the community. This is not a utopian fantasy — it’s already happening in rural communities through art initiatives. Artists are the agents to restore the commons, to bring the soul back to the place that functions as the heart of every small town community.

*Feature image: Early 20th century photo of Main Street Lyons, Nebraska, from the Bill Hedges photo archive.